[ad_1]

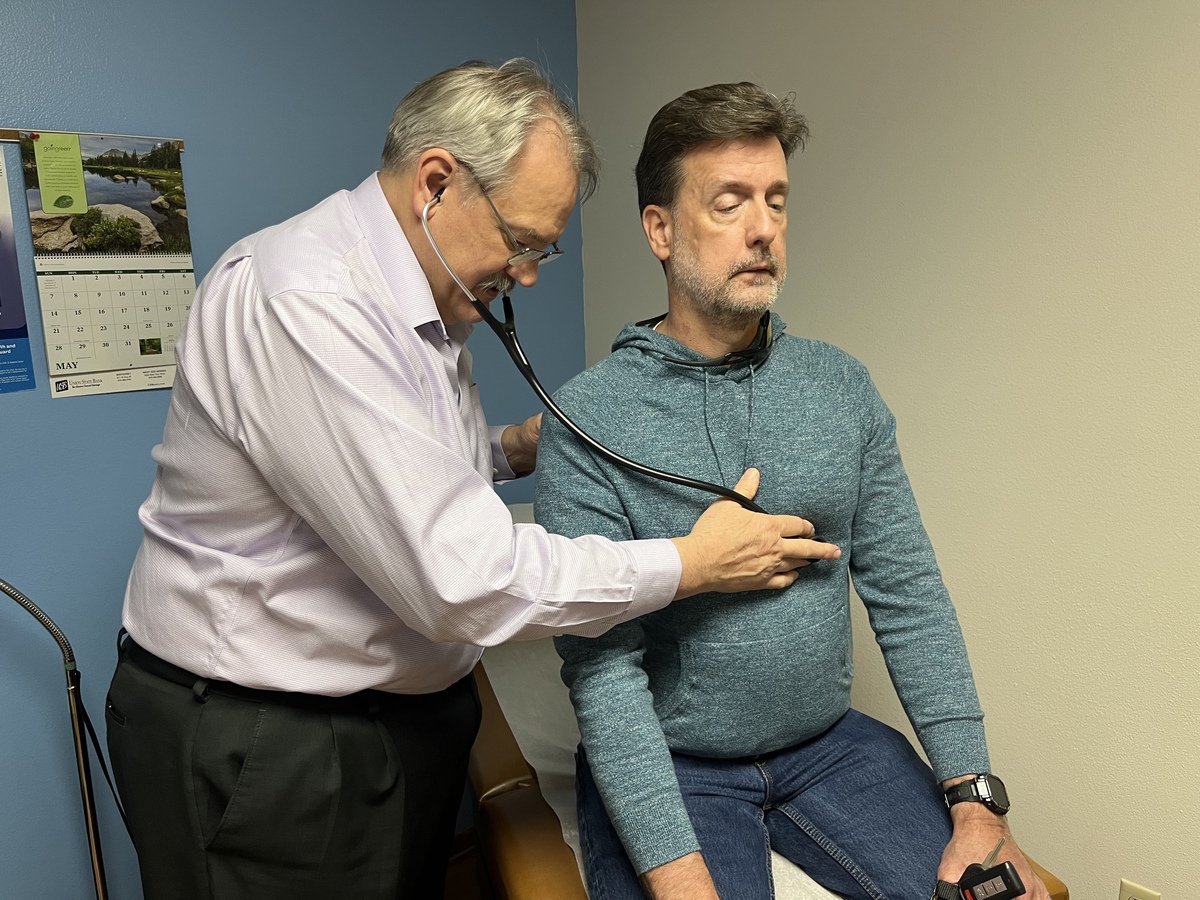

Osteopath Kevin De Renier of Winterset, Iowa, examines Chris Vaughn, who came in on May 9, 2023, to adjust his anxiety medication.

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

Osteopath Kevin De Renier of Winterset, Iowa, examines Chris Vaughn, who came in on May 9, 2023, to adjust his anxiety medication.

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

Winterset, Iowa — For 35 years, residents of this town have brought all manner of illness, pain and affliction to Kevin de Renier’s over-the-counter clinic on Courthouse Square. And he loves its inhabitants.

De Regnier is an osteopathic doctor who chose to run a family-owned clinic in a small community. Many of his patients have been under his care for years. Many people have chronic health problems such as diabetes, high blood pressure and mental health issues, and he helps them manage them before they become serious.

“I decided I wanted to prevent the fire rather than put it out,” he said during a break in an appointment on a recent afternoon.

Widespread shortages of primary care physicians in rural America are partly due to the fact that many physicians prefer to work in highly paid professions in urban areas. In many small towns, osteopaths like de Régnier are helping fill that gap.

Osteopathic physicians, commonly known as DOs, go to a separate medical school from physicians known as MDs. Their courses include lessons on how to physically manipulate the body to relieve discomfort. But their training is otherwise comparable, say leaders in both branches of the profession.

Both types of doctors are qualified to practice all areas of medicine, and many patients have little difference between the two, other than the initials listed after their names.

Osteopathic physician Kevin De Renier has provided primary care for more than 35 years from his office in Courthouse Square in Winterset, Iowa.

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

Increasing share of doctors in the workforce

DOs are still a minority of American physicians, but their numbers are skyrocketing. Between 1990 and 2022, that number more than quadrupled from less than 25,000 to more than 110,000, according to the Federation of State Medical Boards. During the same period, the number of MDs increased by 91% from about 490,000 to 934,000 he.

More than half of DOs work in primary care, including family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. In contrast, more than two-thirds of his doctors work in other medical specialties.

The number of osteopathic medical schools in the United States has more than doubled to 40 since 2000, with many of the new schools located in more rural states such as Idaho, Oklahoma and Arkansas. School leaders say its location and teaching methods help explain why many graduates end up in primary care jobs in small towns.

De Renier noted that many doctoral schools are located within large universities and are connected to academic medical centers. Their students are often supervised by highly specialized doctors, he said. Students in osteopathic schools tend to do their initial training in local hospitals and are often supervised by general practitioners.

US News & World Report ranks medical schools based on the percentage of graduates who work in rural areas. The osteopathy school occupies his third place out of the top four spots on the 2023 edition list.

Osteopathic schools train doctors in need

The School of Osteopathy at William Carey College in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, tops the list. The program, which began in 2010, was deliberately placed in areas that needed more medical professionals, said Dean Italo Subbarao.

Subbarao said most of the William Carey medical students finish their classes and go to hospitals in Mississippi or Louisiana for training. “Students become part of the fabric of that community,” he said. “They understand the power and value a primary care physician can have in a small setting.”

Leaders on both sides of the profession say tensions between the DO and MD have eased. In the past, many osteopathic doctors felt looked down upon by their doctors. Some hospitals did not give them privileges, so they often set up their own facilities. However, their training is now widely considered equivalent, with both types of medical students competing for slots in the same training program.

Michael Dill, director of workforce research at the Association of Medical Colleges of America, said it’s no surprise that graduates of osteopathic schools are more likely to find employment in family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. “The nature of osteopathic training is primary care focused.

Dill said he is confident in the care provided by both types of doctors. “I would be equally happy to see either of them as my personal physician,” he said.

Alice Collins of Winterset, Iowa shows osteopathic doctor Kevin De Renier a blemish on her hand during a doctor’s appointment on May 9, 2023. A surgeon recently removed her tumor from her hand.

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

Alice Collins of Winterset, Iowa shows osteopathic doctor Kevin De Renier a blemish on her hand during a doctor’s appointment on May 9, 2023. A surgeon recently removed her tumor from her hand.

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

Data from the University of Iowa show that osteopathic physicians are replacing rural roles traditionally played by physicians. The university’s statewide Office of Clinical Education Programs tracks health care workers across the state, and its staff analyzed the data for KFF Health News.

The analysis found that from 2008 to 2022, the number of Iowa doctors based outside of the state’s 11 most urban counties declined by more than 19%. Over the same period, the number of DOs based outside these urban areas increased by 29%. With this change, DO now makes up more than one-third of the doctors in rural Iowa, and that percentage is expected to continue to grow.

In Madison County, a picturesque rural area where de Régnier practices, the University of Iowa database lists seven physicians who practice family medicine and pediatrics. Everyone is DO.

De Renier, 65, speculates that the osteopathic profession’s predominance locally is due in part to its proximity to his alma mater, Des Moines University, which operates an osteopathic training center 55 miles northeast of Winterset.

Des Moines University is home to one of the nation’s oldest osteopathic medical schools. The University of Iowa, which has the only medical school in the state, graduates about 150 M.D. students each year, compared to about 210 M.D. students each year.

De Renier, former president of the American Association of Osteopathic Family Physicians, said many patients probably don’t pay attention to whether the doctor is a doctor or not, but some ask for a type of osteopathy. Patients may prefer physical manipulations that DO can use to relieve limb and back pain. And they may sense the specialist’s focus on the patient’s overall health, he says.

“When he sits in that chair, he will be yours.”

On a recent afternoon, Mr. de Régnier saw patients, most of whom had seen him before.

One of them was Ben Turner, a 76-year-old minister from the nearby town of Lollimore. Turner came in for a diabetes test. He took off his shoes and sat on the examination table with his eyes closed.

Winterset, Iowa osteopath Kevin De Renier examines the feet of local pastor Ben Turner, who has diabetes.

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

Winterset, Iowa osteopath Kevin De Renier examines the feet of local pastor Ben Turner, who has diabetes.

Tony Reyes/KFF Health News

Mr. de Régnier took out a flexible plastic probe and instructed Turner to say when he felt it touch his leg. The doctor then began gently placing the probe on the patient’s skin.

“Yes,” Turner said, as the rover stared at each toe. “Yes,” he said as Mr. de Régnier rubbed the probe against the sole of his foot and moved to the other. “Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah”

The doctor gave us good news. Turner’s foot showed no signs of nerve damage, a common complication of diabetes. A blood sample showed good A1C levels, an indicator of disease. He had no chest heaviness, shortness of breath, or wheezing. The problem seems to have been circumvented thanks to the drug.

Chris Vaughn, 55, of Winterset, stopped by to talk to de Régnier about mental health. Bourne has been dating de Régnier for about five years.

Bourne is on medication for anxiety. On his doctor’s advice, he reduced his dose. He told de Régnier with dismay that his anxiety had returned and he could not sleep.

Mr de Régnier noted that the dose he prescribed to Vaughn was relatively low, but he agreed with attempts to reduce the dose. “I’m glad I tried,” he said. “Don’t blame yourself.”

In a later interview, Vaughn said he had never been to an osteopathic doctor before moving to Winterset five years ago, and didn’t even know what an osteopathic clinic was. He came to appreciate de Régnier’s patience in identifying the cause of his patients’ problems.

“When he sits in that chair, he’s yours,” Bourne said.

Another patient that day was Lloyd Proctor Jr., 54, who had previously undiagnosed diabetes. His legs were swollen and limp. A test revealed that his blood sugar was more than four times normal.

“My pancreas is not doing well right now because it’s trying too hard to control my blood sugar,” the doctor told him.

De Renier said he diagnosed Procter with diabetes, prescribed drugs and insulin, and adjusted orders if necessary to minimize Proctor’s post-insurance costs. He pulled out a syringe and showed Proctor how to inject insulin. Proctor listened to advice on how to measure blood sugar.

“Maybe you shouldn’t drink Mountain Dew every time you’re thirsty,” the patient lamented.

De Régnier smiled. “I was just trying to get to it,” he said.

The visit was one of the longest hours for the doctor that day. Finally, he reassured Proctor that together he could control his diabetes.

“I know that’s a lot of information. When you go home and think, ‘What did he say?’ — feel free to pick up the phone and call me,” Dr. Renie said. “We are always happy to visit.”

KFF Health NewsFormerly known as Kaiser Health News (KHN), it is a national news editorial office that produces in-depth journalism on health issues and is one of its core operating programs on health issues. KFFMore — An independent source for health policy research, polls and journalism.

[ad_2]

Source link